It’s Personal

My admiration for Elizabeth Murray began in 1976 in an exhibition at the esteemed Paula Cooper Gallery, which at the time was located in the still-grimy, industrial SoHo. I was simply stunned by Murray’s quirky paintings—often oddly shaped, sometimes less than graceful. The works were simultaneously familiar and unlike anything I’d seen before; they were unforgettable.

Murray’s visual language, her distinctive combination of scale, color, mark, and oddly shaped canvases, synthesized Cubism and Pop sensibilities into something fresh and current. I followed the gallery’s calendar closely to make certain that I was in New York every two to three years to see the progress of Murray’s work—an evolution I was never fully prepared for. Upon meeting her at an opening, I was struck immediately by how genuine and earnest she was; she was as excited about making these paintings, as I was to observe them.

Murray’s painting Wishing for the Farm was first shown at Paula Cooper Gallery in 1992. I saw the exhibition, but remember it more for the overwhelming physicality of the works, rather than for any specific painting. I next encountered the work in 2006 at a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. The show was a wonderful consolidation of Murray’s career achievements including her last work. My third encounter with the painting occurred in 2009 at the Arts Club of Chicago where a guard asked me to leave after spending an hour and a half looking at only a handful of Murray’s works.

My most recent, and most notable, reunion with Wishing for the Farm occurred this year when a generous gift from Ben and Maja Harris offered the museum an opportunity to add a significant work to its collection through a unique challenge. With additional support from Rhonda Seacrest and Donna Woods, Sheldon acquired this painting that draws on all of the energy inherent in the best works by Murray.

Adding an object to a museum’s collection is always an interesting proposition. The organization’s acquisition committee must consider many criteria ranging from the work’s inherent qualities to its potential to advance the mission of the museum. In the case of Wishing for the Farm, Sheldon’s 1963 building presented an additional concern. Although the Phillip Johnson–designed structure is a perfect venue for large-scale paintings, a medium the architect understood and collected actively, its doors accommodate objects of limited scale. With Murray’s work there was always the question: can we get it in the building?

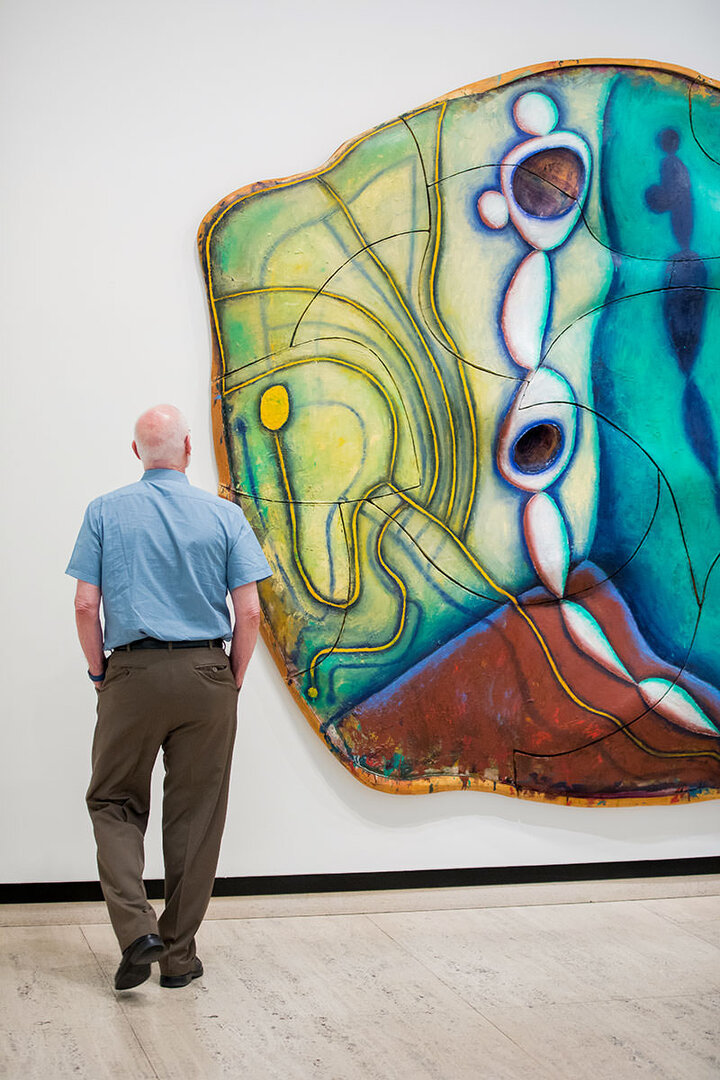

Wishing for the Farm arrived at Sheldon in three crates, a jigsaw puzzle of interlocking canvases that together suggest the topography of rolling hills and deep-cut valleys. Murray’s application of paint is bold, sometimes brash and slightly unkempt, yet always passionate.

It’s virtually impossible to stand before one of her works and not be drawn into the turbulent waves of forms that imply a fraught situation. As viewers, we default to known references that aid us in making sense of these shapes and our relationships to them. The worm-like form that bisects the painting could be from Ghostbusters to one viewer and resemble an endless, whitewashed column by Brancusi to another. Either way, the shadow cast by the form may convey something dramatic and even possibly sinister. The title of the work seems to suggest the desire for tranquility, or at least a respite, in the midst of this topsy-turvy environment that lurches out from the wall into our space.

It’s hard not to be seduced into this painter’s world.

—Wally Mason, Director and Chief Curator

Elizabeth Murray

Chicago, IL 1940–New York City, NY 2007

Wishing for the Farm

Oil and canvas on wood, 1991

107 1/8 × 114 5/8 × 13 1/2 inches

Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, gift of the Hormel Harris Foundation, Rhonda Seacrest, Donna Woods, and funds from the Olga N. Sheldon Acquisition Trust, and the Charles W. Rain and Charlotte Rain Koch Gallery Fund, U-6778.2018